|

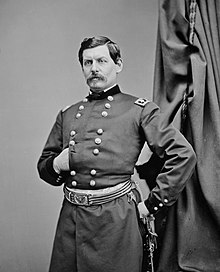

| 1861 photograph by Mathew Brady - Wiki |

Roots in Ripon

Chuck Roots

11 December 2017

The Ripon Bulletin

Recently, I wrote an article about General Robert

E. Lee, commanding officer of the Confederate Army during our American Civil

War. Lee very nearly pulled off the upset of American history by outmaneuvering

the apparently hapless Union generals called upon by President Abraham Lincoln

to carry the fight to the outnumbered Southern forces. By most historical

accounts, the Civil War should have been over in a matter of months, not the

four long years and 700 thousand deaths it extolled from a war-weary nation.

My sister Joy, came over for Thanksgiving last

month, bringing me a couple of magazines she ran across that she knew I would

treasure. As a Civil War buff, I have accumulated over the years a small

library of books, magazines and other items pertaining to this horrific war.

The two magazines Joy acquired for me are both copies of The Civil War Times:

one dated August 1968, and the other August 1962. A section in the 1962 edition

focused on the centennial edition of the Battle of Antietam. The summer months

of 1862 are considered the high summer of the Confederacy. Never again would

the cause of the South and her fight for independence come as close to success

as it did under the leadership of Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Jeb Stuart, and other

notable Southern generals.

Historians argue over the ineptness of Union (or

Northern) military leaders. In my research, I have found two primary reasons

for the Union army failing repeatedly to secure major victories in the early

stages of the war. First, the Northern forces were not defending their homeland

against an aggressor the same way the Southern forces were. This is one of the

reasons the war was referred to by southerners as the “War of Northern

Aggression.”

Second, the Union general selected to head the Army

of the Potomac (later to be called the Union army) was not willing to fight.

General George B. McClellan, like his counterpart of the Confederate army,

General Robert E. Lee, was second in his class at West Point. And like Lee,

McClellan was a military engineer. He never commanded troops in the field

against an enemy until the Civil War. And this was his undoing.

McClellan, referred to as “Little Mac”, attended

West Point from 1842-46. Shortly after graduation he was assigned to fight in

the Mexican-American War. It was during this time that he contracted what he

called his, “Mexican disease,” better known to us today as, “Montezuma’s

Revenge.”

McClellan was viewed as an up-and-comer as a

military officer, serving successfully in every command during his eleven years

of service. During his time in the army, he used his fluency in French to

publish a manual on bayonet tactics that he had translated from the original

French. He also wrote a manual on cavalry tactics based upon Russian cavalry

regulations. The Army also adopted McClellan’s design for a cavalry saddle,

known as the McClellan Saddle. It became standard issue for as long as the Army

had a cavalry, and is still used today in ceremonial events.

Little Mac resigned his commission from the Army

in 1857. He was married to Mary Ellen Marcy in New York City in 1860. During

this time, he was the chief engineer and vice president of the Illinois Central

Railroad, and then president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad.

Civilian life simply did not suit him. He

continued to study battlefield tactics which bolstered his adeptness at

training and preparing soldiers for combat when he rejoined the Army. Prior to

the outbreak of the Civil War, McClellan decided to try his hand at politics.

He supported the Democrat Party’s presidential candidate, Stephen A. Douglas in

the 1860 election. Later, he would run for president as a Democrat in 1864, in

hopes of defeating President Lincoln. He re-entered the Army in the spring of

1861.

One of McClellan’s shortcomings was his

impatience and impertinence toward those who were his superiors. He was

referred to in the press as a “Young Napoleon.” He valued only career military

men, showing utter disdain for volunteers. He often refused to obey political

and military leaders, a tactic that would put him at odds with President

Lincoln early in the war. He snubbed and insulted Lincoln, referring to him as

“nothing more than a well-meaning baboon.”

Oddly enough, McClellan did not come from the

abolitionist point of view, as did many of his fellow officers in the Union

Army. He believed the South should be allowed to practice slavery if that was

their choice. He was vehemently opposed to federal interference in slavery. But

he was just as opposed to states seceding from the Union.

|

| Roots in Ripon - Author Chuck Roots |

But his unwillingness to commit troops in the

field, always believing that Lee had superior numbers, caused him to be viewed

as an inept battlefield commander. Sadly, he spent the remainder of his life

attempting to rewrite his legacy. He died in 1885.

Lincoln’s frustration with McClellan could be

summed up in this phrase: “He won’t fight!” General Ulysses S. Grant referred

to Little Mac as “one of the great enigmas of the war.”

General George B. McClellan simply did not have

the heart of a warrior. And that cost the lives of countless men, both for the

North and the South.

No comments:

Post a Comment

The South Central Bulldog reserves the right to reject any comment for any reason, without explanation.